MAIN REVIEWS

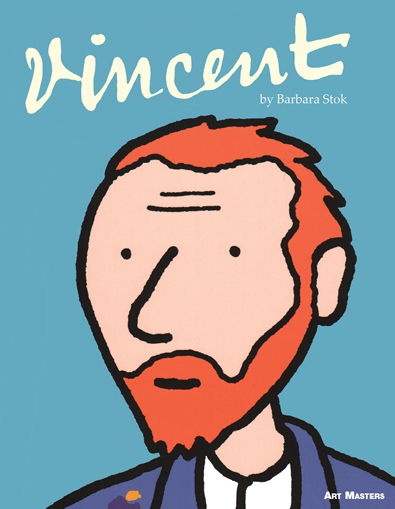

Vincent - by Barbara Stok. Reviewed by Tara Jennett

Banish Your Self-Esteem Thief - by Kate Collins-Donnelly. Reviewed by Mark Edwards

"I'm Sorry For What I've Done" - by M. Catherine Gruber. Reviewed by Joe Sinclair

Keeping Foster Children Safe Online - by Dr John DeGarmo. Reviewed by Michael Mallows

How Children Learn to Write Words - by Rebecca Treiman & Brett Kessler. Reviewed by Penelope Waite.

Attachment, Trauma, and Healing - by Terry M. Levy and Michael Orlans. Reviewed by Joe Sinclair

Attachment and Interaction - by Mario Marrone. Reviewed by Joe Sinclair

Life Coaching for Kids - by Nikki Giant. Reviewed by Mark Edwards

Comedy and Distinction - by Sam Friedman. Reviewed by Sep Meyer

Uncultured Pearls - by Joseph Sinclair. Reviewed by Damlanur Abaan

BRIEF REVIEWS

Twentieth-Century War and Conflict - A Concise Encyclopedia. Edited by Gordon Martel. Reviewed by Joe Sinclair.

Knowledge and Presuppositions by Michael Blome-Tillmann. Reviewed by Joe Sinclair.

Celebrity Culture - by Ellis Cashmore. Reviewed by Sep Meyer

Social Sciences - The Big Issues - by Kath Woodward. Reviewed by Terry Goodwin

Uncultured Pearls - by Joseph Sinclair. Reviewed by Curie Sofia Pereira

Vincent - by Barbara Stok. Paperback. 144 pages. £12.99 ISBN 978-1-906838-79-9. Publisher: SelfMadeHero.

If you ask people to name a famous painter a great many will unsurprisingly say Vincent Van Gogh. Known for his extraordinarily colourful impressionist paintings and his frequents bouts of mental illness (famously cutting off his ear during one of these episodes) it is refreshing to read Vincent as the reader learns a little more about Van Gogh’s life than is usually generally acknowledged.

I found the way Barbara Stok paints Van Gogh, as a person who struggled to find connections in his life, very interesting. Throughout this graphic/manga text Van Gogh frequently makes long speeches about his philosophical views or even just his ideas about creating a “house for artists,” nevertheless it is rare that anyone pays attention or fully appreciates what he has to say. The reader cannot help but feel sympathy for Van Gogh as, though he is a flawed character, watching the boyish excitement he has about his ideas slowly fade during the text is heartbreaking. Fortunately he finds refuge in his paintings and his relationship with his brother, which was the most interesting and uplifting part of the story.

On a slightly negative note in my view the artwork in the novel was not best suited to the subject matter. The artwork was very good but I couldn’t help but feel as though the drawing style was far too controlled when displaying the life of Van Gogh. I thought the pictures should have been drawn with a much freer and impressionistic style that reflected his work. However the way in which Barbara Stok drew certain pictures with elements of Van Gogh’s paintings, such as having dots cover the entire background, when Van Gogh was having a bout of mental illness, was an interesting way to display the turmoil going on in his mind during that time.

Vincent is a short read but an effective one. It explores Van Gogh’s time in Provence giving new information as well as leaving enough unsaid for the reader to be prompted to do further research if they are interested in his life. My last point is that I found it fitting that a recurring theme in the book was the idea of infinity and being remembered by generations after you have passed. Though Van Gogh may not have been acknowledged by many during his time, in modern culture it is clear that Vincent Van Gogh is a figure who will not soon be forgotten.

Tara Jennett

Banish Your Self-Esteem Thief - by Kate Collins-Donnelly. Paperback. 240 pages. £14.99 ISBN 978-1-84905-462-1. Publisher: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

I have to confess to feeling somewhat apprehensive when I see the words 'self-esteem' on the front of a book. There was a time when it seemed to be mandatory to address children's self esteem issues above anything else. I'm thinking perhaps of the late 80s/early 90s when it almost became a craze on a par with the hula hoop or Rubik's cube. Laudable though this enthusiasm may have been, and certainly in many cases sadly necessary, we didn't seem to get a lot further than offering, as one teaching colleague of mine put it, 'bags of praise'. It didn't really work where it needed to, because unlike in Kate Collins-Donnelly's excellent book, the children were not encouraged to be particularly active in the process beyond making a list of things that they were good at. If they struggled with this, there didn't seem to be much else on offer.

Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy is a way of structuring what can often feel like chaos when negativity becomes overwhelming and Banish Your Self-Esteem Thief is a very well-structured book. The first half explains through a mix of questionnaires and psycho - education how feelings and thoughts about ourselves develop. It is encouraging to see the use of time lines, for example, as a means of initiating the process of reflecting on how life experiences and the meanings attached to them can lead to poor self image. Similarly the author acknowledges the influence of our wider culture in creating pressure and insecurity in young people. Throughout this book examples of young people's experiences are shared in a way that the young reader can relate to.

A basic concept runs throughout the book: that of the 'Self-esteem Vault' in which we store positive and negative thoughts and feelings and the Self-Esteem Thief' who runs away with the positive stuff. Thoughts and feelings are linked to actions ; again this is very well structured with examples of the sorts of things that human beings will do in response to negative thoughts and feelings: avoidance, passivity and aggression for example.

The second half of the book shows the reader what to do. It is a combination of 'mindfulness' (rapidly becoming the buzzword of the decade) and using logic. The young person is encouraged to examine the evidence for not just their negative thoughts but the deeper beliefs that underpin them. This is key to the process of CBT ; it is when one starts to challenge one's own negative thoughts that real change is effected.

I don't know what the resource implications are for the publisher but I felt that a CD containing A4 worksheets could have been very useful here. Likewise, there is reference to relaxation and visualisation activities and more detailed examples could have been included as an appendix perhaps.

The author has a talent for presenting concepts in a way that young people will find accessible ; the 'graded exposure' ladder is something that I will be taking away with me. She also acknowledges that this book is not a substitute for face to face therapy and that significant problems will need the involvement of professionals. She cites the growing evidence base for the efficacy of CBT with young people including mindfulness - based CBT.

A rich, informative and practical book.

Mark Edwards

"I'm Sorry For What I've Done" - The Language of Courtroom Apologies - by M. Catherine Gruber. Hardback. 256 pages. £48.00 ISBN

978-0-19-932566-5. Published by Oxford University Press

The Yiddish word chutzpah has been linguistically legitimized to the extent that it now bears an entry in the Standard Oxford English Dictionary [shameless audacity, gall] and no longer needs quotation marks or italicizing.

Leo Rosten in The Joys of Yiddish added to his definition the description of "that quality enshrined in a man who, having killed his mother and father, throws himself on the mercy of the court because he is an orphan".

This could almost be incorporated as a 53rd allocution to add to the 52 that M. Catherine Gruber has described in her book, but – and this should come as no surprise – the word does not appear in the index.*

Actually the term "allocution" is generally only in use in jurisdictions in the United States. In England we tend to employ a long-worded expression such as "pre-sentencing statement in mitigation", whereby it might be suggested that . . . “Before I pass sentence, is there anything you would like to say in your own behalf?”, though there are vaguely similar processes in other countries. In some jurisdictions it is the defence lawyer who may mitigate on his client's behalf, and the defendant himself will rarely have the opportunity to speak.

Allocution is important because it is the one opportunity within the criminal justice system where a convicted defendant is offered the chance to speak. And this —the penultimate stage of a criminal proceeding at which the judge affords defendants an opportunity to speak their last words before sentencing—is a centuries-old right in criminal cases. At common law, the defendant in a felony case had a right of allocution—the judge asked the defendant whether he had any reason to offer why judgment should not be entered against him.

The 52 apologetic allocutions examined by Gruber differ from each other in several ways such as the nature of the offence, excuses for the offence in mitigation, promises not to re-offend, and attempts to influence the sentence. A considerable amount of “guesswork” is involved in trying to establish just how effective these allocutions may have been, since there is never a comment forthcoming from judges about how far these attempts at mitigation have succeeded in reducing sentences that might have been imposed without them.

The author uses case law, sociolinguistic and historical resources, and judges’ final remarks to develop hypotheses about defendants’ communicative goals as well as what might constitute an ideal defendant stance from a judge’s point of view. She applies the J.L. Austin exposition of the difference between the performative and the constative utterance to analyse the differences between the various forms of allocution at sentencing and how each may effect or effectively constrain the aims and achievements of defendants.

In How to Do Things with Words, [The William James Lecture delivered at Harvard University in 1955] J. L. Austin attempts to distinguish between a constative and a performative utterance. The important distinction between these is that while the former reports something, the latter does something. A performative denotes an action. It is a promise. It may or may not be kept. Thus: “I promise to obey the rules.” Again, “I apologise” is a performative utterance. A constative utterance, however, might be an admission that the defendant performed an illegal act.

In this respect, therefore, Gruber suggests that a constative statement about their offence is likely to have a much better impact on the court, since it “allows defendants to perform their remorse as opposed to proclaiming it.” And this then is the background against which the author considers the effectiveness of the variety of allocutions. Gruber considers that although a ritualized formula such as “I’m sorry” or “I apologise” is a recognised – and even expected – form of allocution, it may not best serve the defendant’s interests. These are better served by the constative offence-related utterance. She also believes that, implying that one is sorry is more effective than explicitly claiming to be sorry.

In the first chapter of the book, Gruber informs us that "Defendants' apology statements lasted from 4 seconds to 186 seconds, with a median allocution time of 29.5 seconds. Defendants did eight basic kinds of things during their allocutions . . .

1. ACCEPTANCE: Defendants accepted the invitation to make an allocution . . . [such as politeness] . . . "Thank you"; "Your Honor" . . . [or not] . . . "Yeah" or"Yes I would".

2. METACONTENT: Defendants broke the frame of allocution by referring to the context of the sentencing hearing, such as "Can I stand up?"

3. THANKS: They thanked family and friends for their support.

4. OFFENSE: Defendants assessed and/or criticized their actions . . . often by means of some sort of apology.

5. MITIGATION: Defendants offered information they hoped would mitigate a harsh sentence . . .

6. FUTURE: Defendants . . . referred to positive things they hoped to do, or they claimed . . . to have learned a lesson from the experience.

7. SENTENCE: They referred to the sentence [usually] to request lenience.

8. ENDING: They ended their turn at talk, sometimes with . . . polite terms of address for the judge, such as "That's it, Your Honor."

(This 'coding system' is given a much more detailed treatment in Appendix 2 of the book.)

One of the author's contentions, as revealed in subsequent chapters, is that the history of allocution suggests it was introduced as a protection for defendants by giving them the opportunity to speak before sentencing, whereas it actually offers significant benefits for the state and limited benefits for defendants. She considers the alternative merits of offering a conventional apology, such as "I'm sorry", as opposed to offering mitigating information, asking for leniency or "another chance". Sometimes they might assert that they would accept whatever sentence was imposed, but this could be interpreted as an attempt to diminish "the taint of one's institutional role identify".

A particularly intriguing section of Gruber's book - at least for this reviewer - is Chapter 6, where the author examines the use of non-standard language, "relatively infrequent use of politeness markers, and relatively frequent use of the adverb 'just'. The paralinguistic features of wavering voice and crying while talking patterned with gender: while the voices of 3 (of 41) men wavered briefly, 7 of 11 women cried during their allocutions. . . . Thus, for example, when “just” restricts a metapragmatic frame of speaking (e.g., “I just wanna say that I’m sorry”), that restriction can be interpreted as either limiting what the defendant is able to say or as what the defendant is willing to say. These interpretations have very different implications for the defendant’s stance. "

Although the book may be somewhat more significant in terms of the American rather than the British legal system, its main interest is in its linguistic - and particularly its paralinguistic - content, and I have no hesitation in recommending it to any student of language.

* Judge Alex Kozinski and Eugene Volokh in an article entitled Lawsuit Shmawsuit, published in the Yale Law Journal in 1993, note the rise in use of Yiddish words in legal opinion, and argue that Yiddish in quickly supplanting Latin as the spice in American legal jargon. They note that chutzpah has been used 231 times in American legal opinions, 220 of those subsequent to 1980.

And here’s another legal chutzpah story. A man goes to a lawyer and asks: "How much do you charge for legal advice?" "A thousand dollars for three questions." "Wow! Isn’t that kind of expensive?" "Yes, it is. What’s your third question?"

Joe Sinclair

Keeping Foster Children Safe Online - by Dr. John DeGarmo. Paperback. 160 pages. £12.99 ISBN

978-1-84905-973-2. Published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers (1)

John Degarmo has fostered more than 40 children and written a number of books that are intended to improve and promote successful foster and adoptive care systems.

This book provides a wealth of information, good and ghastly, about the dangers and risks that foster carers, adoptive and biological parents, teachers, youth workers, social workers and others who work with, teach or live with preteens and adolescents really ought to know!

The genie is out of the box, and it is unlikely that it can ever be put back.

This book should be read and re-read and information shared - as appropriate - with fostered, adopted and biological children because, as the book explains, you could be at risk of accusations, and ignorance might not be an acceptable excuse!

There is a specific focus on foster children, not least because of the ease with which they can locate and contact birth relatives or others whose previous [abusive] interaction with the foster child required the young person to be removed to a safer environment - this can be the case with any youngsters - and adults, of course - whose self worth and self confidence has been eroded by dysfunctional parents or other adults whose parenting skills were very poor, non-existent, or dangerous as a result of their own upbringing.

Even very young children often know more about technology and

cyberspace than the adults who care for them. Social media such as Facebook,

makes it relatively easy for savvy youngsters to find people who could pose

potential threats to young people. An online presence creates unique challenges

for foster carers and children and their caseworkers.

According to a recent Nielsen survey, the average teen aged between the ages of

13 and 17 sends 3417 texts per month; the average teenage female sends 4050

texts per month; the average teenage boy sends 2539 texts and some teens send

more than 10,000 monthly! Think of the number of texts you might send on a busy

day…

Sexting (sex and text) means sending sexually suggestive messages, pictures,

even videos from one electronic device to another. The recipient might reply

with a nude picture.

Do not, warns the author, believe that you can prevent or protect youngsters

from this kind of behaviour; gadgets are everywhere and friends can share their devices with each

other when they get together

Foster carers, adoptive parents, professionals need to learn about the real and ever present dangers that proliferate online. Carers will, inevitably, find some shocking, disgusting and alarming images and messages. When that happens, rather than ‘flying off the handle’ it is better to stay calm, or at least take a few deep breaths so that they can engage in a rational discussion, however uncomfortable or embarrassed they might feel.

Sexting is becoming more acceptable to today’s youth, starting with children as

young as nine. Apparently it is today’s form of flirting; 28 percent of

teens have sent naked pictures of themselves via email or cellphone. 57 percent

have asked other teens to send a sext message. Some of these images might

be due to peer pressure or to improve social status. And, of course, cyber

bullying is rampant, and getting worse.

The author gives very good advice on how to know what sites your child is

accessing and how to block access. The author is very clear that this is not an

invasion of privacy, it is protecting young people from the many risks including

undesirable people and images. Youngsters will need openness and honesty rather

than hysteria, and this is what this book offers, in a matter of ‘fact’ way.

The author emphasises the need to communicate with case workers with regard to

certain requests for games and gadgets. He is even more emphatic about making it

clear to foster children (and others) that anything posted on the net is there

FOREVER!

The following news item illustrates how youngsters can, through ignorance and innocence, get entangled in the world wide net and be forever paying a terrible and unexpected price.

You may recall a story, just a few weeks ago, about a schoolgirl who sent a topless picture to her boyfriend. The boyfriend showed the picture to his friends and both received police cautions for committing the offence of ‘distributing an indecent image of a child’ because they were both under 18!

Having been a foster carer myself, I cannot highly enough recommend this book to anyone who lives or work with young people - not just foster children.

Michael Mallows

(1) The book's subtitle is Positive Strategies to Prevent Cyberbullying, Inappropriate Contact, and Other Digital Dangers. The book carries a foreword by Kim Phagan-Hansel

How Children Learn to Write Words - by Rebecca Treiman & Brett Kessler. Hardback. 416 pages. £52.00 ISBN 978-0-19-990797-7. Published by Oxford University Press

When browsing this book, prior to settling down to a thorough reviewing study, I was struck by “. . . literacy learning begins long before children can write themselves. Children in literate societies are surrounded by examples of written language from an early age, on cereal boxes, in storybooks, on street signs, and so on.” [p.103]

And I was then struck by a long-forgotten but happy memory of a small child (perhaps two years old) pointing to a word in a magazine article and saying "Persil". "How do you know that?" I asked, and she ran over to the sink and brought me the bottle of washing-up liquid, and pointed to the label. This story was recounted with great pride for days, until consigned to the oblivion where it has resided for the past 40-plus years.

This in turn reminded me of something I had read some years ago, that seemed perhaps apposite, and I checked it out on Google. It came from the Donald H. Graves book Writing: Teachers and Children at Work (1983): "Children want to write. They want to write the first day of school. This is no accident. Before they went to school they marked up walls, pavements, newspapers with crayons, chalk, pens or pencils… anything that makes a mark. The child’s marks say, 'I am' "

The authors of How Children Learn to Write Words are linguists and psychologists, professors at Washington University in St. Louis, USA. Their proclaimed aim in writing this book is "to examine what types of writing systems exist in modern societies and how children learn to use these systems for purposes of production. We discuss how children learn about such things as the shapes and names of letters, the spelling of unusual words, and capitalization and punctuation." [p.1-2] They also say [p.22] “Our interest . . . is in the learning of orthography by children who are neurologically and perceptually unimpaired.” [and] “We are interested in the learning of orthography by children in modern literate societies, and so almost all of the data that we review comes from mainstream children in these societies.”

They place writing in the context of all the other communication tools that have been developed, and on page 117: "Children in modern literate societies begin to learn about some of the outer or formal properties of writing as early as 1 or 2 years of age. They start to learn what writing looks like, and they start to learn how it differs from pictures. Children begin to do this before they have received any formal literacy instructions and before they understand much, if anything, about how writing symbolises units of language."

For me, the most significant section of the book is section 4.6. I.M.P., starting on page 97. I.M.P. is the Integration of Multiple Patterns where, in children's acquisition of writing skills, they learn about both the spelling of individual words and about general patterns. Thus when learning about patterns in an orthography, children apply their general-purpose learning mechanisms, such as statistical learning, i.e. "tracking how often and under what conditions events [such as certain word endings] occur"

The importance of this theory is illustrated by a paragraph on page 99, "IMP predicts that children in literate societies, who have extensive exposure in print from an early age, will begin learning about some of its salient formal properties quite early. To begin learning about the patterns that relate written symbols to their linguistic functions, however, children must first learn that writing stands for something outside itself. They must treat language as something that can be symbolized, and they must break up spoken words into units of the type represented by their writing system. Given the difficulty of these tasks, IMP predicts that children will typically begin learning about the links between graphic forms and linguistic units only after they have begun to learn about some of the more obvious formal characteristics of writing."

One of the things I was looking for - in vain - in this book was how the authors might have treated the effect that modern communication methods are having on the writing skills of children whose exposure to these methods, particularly electronic devices, seems to start ever earlier and earlier in their lives. The only option would appear to be to apply the theories that are proposed and conclusions that are reached to our own experiences of these effects, and particularly the experiences of educators. Texting clearly has an absolute, one might even say disastrous, effect on orthography, and since this is the aspect of electronic communication to which children will be most greatly exposed, one might suppose that Treiman and Kessler would fulminate against it. As well, however, to emulate Canute. Similarly, of course, for cyber slang, using symbols such as 2 for to, too or two, or the abbreviation "u" for you. But these issues are not addressed by the authors. Pity. But it was, presumably, well outside their brief

I am only too unhappily aware that this is a less than scholarly review. My imagination was captured by the advance notice of its publication and I anticipated something less academic. I have been far from disappointed, however, despite the preceding paragraph, by the wide-ranging coverage, including an historical consideration of orthography, as well as the requirements for developing writing skills, making it of greater interest, perhaps, to psychologists and linguists than to educators. Nonetheless it more than merits a place on the shelves of the staff library of our teaching establishments.

Penelope Waite

Life Coaching for Kids by Nikki Giant. Paperback. 216 pages Price £17.99. ISBN: 978-1-84905-982-4. Published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers

I have to confess that I approached this book with a certain degree of trepidation. 'Life coaching' is a term that I became aware of during the late nineties and early noughties when the industry began to grow. I read a few books and articles on the subject at the time and also recall a phone conversation I had with an aspiring life coach who assured me confidently that counselling and psychotherapy were 'on the way out' and now basically old hat. Further to this the books that I read (and that later lined the shelves of my local charity shop) seemed to consist for the most part of 'inspirational' tales of people who had made startling and frankly almost unbelievable transformations to their formerly routine and mundane lives following a few sessions with a life coach.

Maybe I read the wrong books, or maybe we have moved on; whatever the reason, I found Nikki Giant's book to be a bit of a revelation. Not because the content is particularly new to me - it isn't - but because it is communicated in a way that not only respects the differing strands of therapy but also makes very clear the distinction between coaching and therapy, and without attempting to claim superiority of one particular approach. She makes it very clear in her introduction that although coaching can be carried out by people who are not trained counsellors, the skills of counselling and other therapies are central to the art of coaching. She also manages to perform a sort of synthesis of techniques that have developed from various different (though related) approaches, including CBT, NLP and Solution Focused Brief Therapy.

The first part of the book explains how life coaching has developed as a tool to aid personal development. It is very much about setting personal goals and making plans to accomplish them. Activities to encourage self-awareness are central; coaching is not something that is done to you, it is done with you and there is a lot of hard work involved. It will not be effective unless the young person is motivated to make changes. Having said that the activities and worksheets are presented in a way that are likely to attract the interest of young people.

There is an acknowledgment in the book of the increasing pressures and stresses that 21st century life places upon youngsters, and this makes reference to solid research. The author is also at pains to remind the reader that life coaching is an unregulated profession and that the emotional safety of children and young people is paramount; hence, if there are indications that distress is related to trauma or an abusive home environment, then specialist advice should be sought. Similarly, although the techniques used in life coaching draw on established therapies (such as CBT) they are not a substitute for this when a deeper level of engagement may be needed.

The second part of the book consists of activities and worksheets and is structured thematically; for example a section on bullying and one on confidence. Many of these will be familiar to therapists and counsellors who work with children and include suggestions for structuring experience through techniques such as scaling which I have personally found to be a highly effective tool. Others include specific visualisations and relaxation exercises.

My only real criticism of this book is one of format. As a sizeable portion of the book consists of worksheets I feel that a spiral - bound publication would be more practical. Aside from this Nikki Giant has produced a resource which if used appropriately and sensitively could greatly enrich the lives of adults and children.

Mark Edwards

Attachment, Trauma, and Healing - by Terry M. Levy and Michael Orlans. Paperback. 477 pages. £25.00 ISBN 978-1-84-905888-9. Published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

This is the second edition of a book first published in 1998. Not having read the first edition, I am unable to compare the two and judge how effective the changes have been. What I do know however is that the original edition of the book had acquired a considerable reputation and had, in effect, become a classic in its field. I also know, from having contributed to the study of Attachment Theory that is part of the latest New Nurturing Potential issue in which this review appears, that there has been a great deal of development in the field of family therapy and interpersonal relationships in the past two decades. It was with considerable enthusiasm, therefore, that I undertook the review.

I have not been disappointed.

What appealed to me most was the fact that this book goes far beyond the range of source books that had been used for New Nurturing Potential's research into the Main Theme article of its current issue (Attachment Theory), although it does start off - as do all the others - with the historical debt owed to John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth and others.

This is not surprising, given the authors' association with the Evergreen Psychotherapy Center, the Attachment Treatment and Training Institute of Evergreen, Colorado that describes itself as leaders in helping children, adults and families with trauma and attachment problems. The Center's website explains that "disrupted and anxious attachment not only leads to emotional and social problems, but also results in biochemical consequences in the developing brain. Infants raised without loving touch and security have abnormally high levels of stress hormones, which can impair the growth and development of their brains and bodies."

They further suggest that

"the neurobiological consequences of emotional neglect can leave children behaviorally disordered, depressed, apathetic, slow to learn, and prone to chronic illness. Compared to securely attached children, attachment disordered children are significantly more likely to be aggressive, disruptive and antisocial. Teenage boys, for example, who have experienced attachment difficulties early in life, are three times more likely to commit violent crimes."And this is the area that I found of greatest interest, personally, in this book. Also their reference to the "neurobiological consequences" bears very much on the area of greatest change from the first to the second edition of the work, as well as the impact of attachment on brain development, trauma and later relationships; and how it affects aggression, control and conduct disorders and children's antisocial behaviour.

Particularly impressive was Chapter 5 - Disrupted Attachment - dealing with antisocial behaviour springing from violence and abuse. It must be admitted that this is in the light of American experience, and I found myself trying to identify and associate the authors' findings in this connection with my knowledge of similar conditions in Great Britain, particularly when I came across such passages as "The United States is consistently ranked among the industrialised countries with the highest rates of overall violence . . . [and] . . . high rates of traumatization of children through abuse and through the violence they witness in homes and communities." (p.110) "Children are routinely the victims of violence . . . infants, toddlers and children who experience and/or witness violence in their homes are seriously affected. More than three million children witness parental abuse each year." (p.111) On balance, I have to say, that although the scale of violence and exposure to violence may differ, I doubt that the incidence of it and its impact differ significantly between the two countries.

This is really one of the most heinous and horrifying aspects of disrupted attachment, and it is good that Levy and Orlans have given so much prominence to it. In researching the article in New Nurturing Potential, I came across this statistic: "15.5 million children in the United States live in families in which partner violence occurred at least once in the past year. Being exposed to one type of violence puts children at an increased risk of being exposed to other violence. This is known as polyvictimization."

One can do nothing but applaud any works that are involved with identifying the causes of antisocial behaviour, particularly where it affects the young and helpless, who - because these disorders and transmitted inter-generationally - will grow up to be parents who may themselves abuse, neglect and abandon rather than cherish, love, protect and nurture their offspring. Although it really forms no part of this review, I want to acknowledge the satisfaction I got from my reading of Dr. Levy's contribution in the Handbook of Attachment Interventions (Academic Press, 2000) on Attachment Disorder as an Antecedent to Violence and Antisocial Patterns in Children.

The nine appendices that comprise a number of charts, forms, questionnaires and studies are impressive and I suspect these may not have changed much, if at all, from the earlier edition. They seem mainly to derive from the work the authors undertake with the Evergreen Psychotherapy Center, with which they are associated. It may, indeed, be worth buying the book for these alone. But, no! There is so much more to be gained for parents, trainers, families, therapists and others. The appendices are a bonus!

Joe Sinclair

Attachment and Interaction - From Bowlby to Current Clinical Theory and Practice - by Mario Marrone.

Paperback. 320 pages. £25.00 ISBN 978-1-84-905209-2. Published by Jessica Kingsley Publishers.It's not just a happy coincidence that this review will appear in the same issue of New Nurturing Potential as does the Main Theme article (Attachment Theory) on what is effectively the same subject. The fact is that it was requested for review precisely for that reason. What is, perhaps, a little bothersome is that the book is such an accessible introduction to the history and evolution of attachment theory that we might have simply referred readers to the book rather than produce the article.

The article's second paragraph states that "Just about every description of attachment theory starts with John Bowlby (1907 - 1990) who originally developed the theory" and Attachment and Interaction is no exception to this statement. Indeed, the author Mario Marrone was actually a student of John Bowlby and uses this fact in an occasional anecdotal fashion. And Bowlby features throughout the book.

The book is the second edition of the 1998 publication by the same publishers. It's very readable as it traces the history of attachment theory from its beginning up to the present day from a therapeutic rather than an academic perspective. The first eight chapters cover the history of the theory, its basic concepts, and the contributions by others to its development. Such eminent names, predominantly psychoanalysts, include Eric Rayner, Peter Fonagy, Daniel Stern, R.D. Laing and Anna Freud.

Chapter 9, in which Nicola Diamond joins Mario Marrone, discusses the phenomenon of transference, originally introduced to psychoanalytic theory by Sigmund Freud, and its background aspects. Transference is the redirection of feelings from one person or object, most frequently derived from childhood memories, towards another. This was initially considered inappropriate by Freud. In this chapter Marrone and Diamond consider how the views of others, such as Melanie Klein and Jacques Lacan, have modified our thinking as far as transference, particularly in an attachment context, is concerned.

Throughout the book, the author/s introduce examples and studies showing the inter-relationship between attachment and contemporary psychoanalytic theory, never straying too far from Bowlby and his influence. In Chapter 13, Marrone introduces us to the application of attachment theory to group psychotherapy. As a one-time and very active member of the Group Relations Training Association, I found this chapter of particular interest. I resonated considerably with the statement "once a small group of people gather together and begin to communicate and meet on a regular and continuous basis, one of the dominant phenomena that occurs is that a new micro-social system is established. . . This new micro-social system is a place in which, inevitably, individuals' existing working models are reactivated and brought into play. In this way each group member presents different notions and ideas, different perceptions, and ways of understanding the world". (p.235) This chapter also describes the group use psychotherapeutically of the psychodrama as a way of associating, activating and sharing feelings and thoughts.

The final chapter, Chapter 16 On Bowlby's Legacy, is contributed solely by Nicola Diamond wherein she considers the way John Bowlby's theories conflicted with the psychoanalytic orthodoxy of his time and the points of controversy that he raised. She then discusses the philosophy of attachment theory and precedes her conclusion with a section on Attachment and Sexuality.

The book ends with a substantial - 17 page - reference section.

Unlike the preceding review, this is not a book for the general public, but will be of considerable interest to academics and individual, group, and family therapists.

Joe Sinclair

Comedy and Distinction - The Cultural Currency of a "Good" Sense of Humour - by Sam Friedman. Hardback. 228 pages. £85.00 ISBN 978-0-415-85503-7. Published by Routledge.

I start off with a prejudice that I feel obliged to disclose.

As an alumnus of the London School of Economics I am instinctively inclined to favour works produced by writers associated with that institution, particularly in the academic arena. So Sam Friedman starts off with a considerable advantage.

But that prejudice is fast being overtaken by another growing prejudice that I feel equally obliged to declare. I am rapidly developing the feeling that many students engaged in social media studies have simply “gone for the easy option”.

So is Friedman able to overcome this latter prejudice and convince me that his work is to be taken seriously and is worthy of study? Well, I do believe he has! Certainly his book is a thoughtful and thought-provoking study which, though relating to popular culture, is addressed to an academic audience and I doubt that those looking for an “easy option” will find this an “easy read”.

Friedman has started from a simple premise, firstly that comedy in Britain is booming, secondly that the popularity of comedy has responded to changes in comedic style over the years, and finally that the popularity of those different styles reflects differences in the class structure of their audience. He has set out to identify those changes and differences and attempt to categorize them.

His book is massively underpinned by Pierre Bourdieu's philosophical study La Distinction, and he admits [Appendix 1] to being strongly influenced by Bourdieu’s methodological approach of employing “a range of methods to investigate cultural taste, using survey analysis alongside interviews, textual analysis and photo analysis.” Friedman has stated his aim as being to investigate whether an updated version of Bourdieu's theory of distinction may be relevant when examining taste for contemporary British comedy.

Pierre Bourdieu's work emphasized how social classes, especially the ruling and intellectual classes, dictate their artistic choices and preferences in such areas as music, food, culture and the arts. Friedman has explored this relationship between social class and differing styles of comedy, and he has considered how far differing "cultural capital" dictates taste in comedy. The concept of cultural capital is a key feature of Bourdieu's La Distinction. Friedman did the greater part of his research for this book at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe theatre. In his survey of the different class of audience for comedy performances, the author has divided them into High Cultural Capital (HCC), Mixed Cultural Capital (MCC), and Low Cultural Capital (LCC). In Appendix 2 of the book Friedman identifies his "Cast of Characters" separated into those three categories. These people were asked about their comedy preferences and their patterns of taste in comedy was correlated with their social class, gender, ethnicity and geographical location.

His survey revealed a wide division of response and taste that clearly related to the different levels of cultural capital which, in turn, could be traced back to what they had inherited culturally through their home and family environment. In an interview, Friedman has stated that "parents might talk about cultural topics at home, or take their children to places of aesthetic interest such as museums, theatres or art galleries. Moreover they do not just introduce their children to culture, they also teach them to look and listen in specific ways."

His survey findings revealed "that the most powerful comedy taste distinction separated people with high cultural capital (HCC), particularly younger generations, who tended to prefer critically-acclaimed comedians such as Stewart Lee, Mark Thomas and TV comedies such as Brass Eye and The Thick of It, from those with low cultural capital (LCC), particularly older generations, who tended to prefer comedy that was much less critically legitimate such as Roy ‘Chubby’ Brown, Jim Davidson and Bernard Manning. This taste division was important because it both contributed to, and reflected, the construction of certain comedians as ‘special’ cultural objects – tastes that communicate a sense of cultural distinction."

His statistical conclusions about comedy taste, related to specific comedians, and revealed in Appendix 3, follow Bourdieu's example using Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA). The range of comedians and comedy shows is wide - more than 30 - and diverse, including Eddie Izzard, Michael McIntyre, Russell Brand, Frank Skinner, Jim Davidson, Karen Dunbar, Stewart Lee, Roy Chubby, Bernard Manning, Mr Bean, Monty Python, the Bob Monkhouse Show, Yes Minister, Little Britain, and the Benny Hill Show.

His final appendix [Appendix 4] lists all the comedians and comedy TV shows mentioned in the book and here, having merely looked at the first of these names - Alan Bennett - I immediately took exception to Sam Friedman. He describes Bennett as "an English comic novelist, playwright and actor, best known for his role in the satirical revue Beyond the Fringe." Shame on you, Mr Friedman! How did that impartial approach that you described in the section on Multiple Correspondence Analysis come to desert you? What sample did you take to establish that Bennett is "best known for . . . "? Personally I know him best for his Talking Heads" series. But I might equally have chosen his vast range of TV plays and film credits. I would have taken no exception to "first known for . . . Beyond the Fringe", however.

But this is a minor quibble, and I do not want it to detract from a positive review of a book which, despite my earlier expressed misgivings, succeeded in overcoming all prejudices and produces a "highly recommended" rosette, particularly for students of sociology and cultural studies.

Sep Meyer

Uncultured Pearls - by Joseph Sinclair. Paperback. 126 pages. Published by CreateSpace in the USA. (ISBN 9781500949723). Price US$8.96, and by ASPEN-London in the UK. (ISBN 978-0-9513660-7-3). Price £5.95.

A verse from Joseph Sinclair's Uncultured Pearls:

“There is so much I must say,

so little that I may

And mind, stagnated, lends itself

to physical decay”

Mr. Sinclair’s poetry “uncultured pearls” is anything but. The contradictory name made me appreciate the real pearls that are the poems in this book. It is in the natural, genuine shelled molluscan mind that these pearls of a prolific, yet humbly embellished, wisdom manifest.

I have always been an admirer of skillful wordsmiths from Great Britain. Here we have a poet whose words are indeed tools to create a weapon of deep sincerity. Some of his poems had me thinking that each line is like a proverb.

Like the quatrain above,the wisdom of truth of our limited time on this earth comes across with words simply used to convey the sadness for truth of impermanence.

Having lived in Hong Kong for nine years at the time of her repatriation to China proper, I felt the fabrication of that place thoroughly while reading his poem “Hong Kong expatriate to his love” All that I felt during my stay there is in the poem.

As he described the hopelessness for humanity I felt lost again in the buying/selling fever of the region: the pollution of falsehood packaged in glitter of famous brands, as ones success is measured by the brands of the cars or the watches acquired.

Mr. Sinclair is a masterful user of words. With this mastery he tells us stories with the simplicity of long thought out observations. He allows us to see into the depth of his soul’s growth through the eloquence of his words.

Damlanur Abaan

Twentieth-Century War and Conflict: A Concise Encyclopedia - Editor: Gordon Martel. Paperback. 440 pages. £19.99 ISBN 978-1-118-88463-8. Published by Wiley-Blackwell

This may seem like a minor cavil – even a petty quibble – but, perhaps because the book is really such an excellent example of what it’s designed to be, I felt somewhat disappointed at an obvious omission.

The 2nd Boer War, or The South African War as some historians prefer to know it, was really a 20th century war as it occupied only two months of the preceding century, but endured for two years of the twentieth. Its omission from this encyclopedia is disappointing for two general reasons and one personal reason. The terms guerrilla warfare and concentration camps may be traced back to this conflict, and the subsequent – much later – introduction of the apartheid regime may also owe much in its origins to peace conditions that followed the war. On the personal side, a minor point, I looked in vain for some reference to the role of transport, supply and logistics in any of the conflicts in view of my own research into these areas(2).

Having got that off my chest, I have nothing but praise for the way in which the publishers – and the editor – have reduced an award-winning 5-volume Encyclopedia of War to 440 pages of fascinating and well-written (and edited!) articles by a host of perfectly qualified academics. And, I suppose, some areas have inevitably to suffer from such a degree of compression. A detailed description of the book and its contents will be found at http://eu.wiley.com/WileyCDA/WileyTitle/productCd-1118884639.html .

So, if this is your area of interest, and you begrudge the space occupied by 5 large volumes, then this slim, but well-packed paperback deserves a well-merited place beside your desk.

Joe Sinclair

(2) Is it inexcusably immodest of me to use a review of someone’s book to draw attention to one of my own? Arteries of War by Joseph Sinclair, 1992

Knowledge & Presuppositions - by Michael Blome-Tillmann. Hardback. 224 pages. ISBN 978-

0-19-968608-7. Price £35.00. Published by Oxford University Press.I am starting off with the belief that this book is intended for an academic readership and is unlikely to be of wider general interest. The intended reviewer, alas, has been unable to produce his review and I am therefore writing a "simplified" version for this brief review section.

Blome-Tillmann, a researcher at the University of Cambridge and Associate Professor of Philosophy at Canada's McGill University, has produced this account of presuppositional epistemic contextualism, which is a position about knowledge attributions, that is statements attributing knowledge and denials of knowledge. The truth in knowledge-ascribing and knowledge-denying sentences may vary according to the context in which they are uttered. Two simple examples: "That butterfly is large, but that elephant is not large"; and "If you have a car, Detroit is nearby, but if you are on foot, it is not nearby." (p.132)

Jonathan Ichikawa** in an online article entitled Quantifiers and epistemic contextualism gives an amusing (to me) example of two people watching, from opposite sides of a circus ring, a performance involving clowns emerging from a car driven by a clown. On one side the viewer remarks, after several clowns have emerged, "That's the last of them". On the other side a viewer, watching the driver, comments there's still a clown in the car." They are both right. They both "know". It is the context in which they are uttered that has changed.

Thus epistemic contextualism maintains that whether one knows is in some way relative to context. It explains why in some contexts we judge that we have knowledge, and in other contexts we may judge that we do not have knowledge. Having developed his theory of contextualism, Blome-Tillmann then provides his suggestions as to how it best solves the puzzles and paradoxes generated by sceptical arguments.

Despite my earlier statement that the book is unlikely to be of general interest, I think you may take that in context. [Pun intended!] It is quite likely that a general readership will find much of interest and enjoyment in the subject matter and the author's treatment of it. As for the academic readership, particularly in the field of philosophy - and even more narrowly that of epistemology - I suggest it is a "must-read".

** http://www.jonathanichikawa.net/

Joe Sinclair

Celebrity Culture - by Ellis Cashmore.

Paperback. 404 pages. £27.99 ISBN 978-0-415-63111-2. Published by Routledge.What is celebrity culture and why has this phenomenon become so important to us?

Personally, I don't believe it is a sudden phenomenon, nor that is more important now than in the past. I simply believe that the explosion of the media industry in the last sixty years has succeeded in bringing "celebrities" into our living rooms, and that the increase in leisure time - hence also leisure activities - over the same period has so diminished public taste that people who may have been nonentities in the past have now become notorieties.

Celebrities always existed: Herodotus, Plato, Julius Caesar and Jesus Christ, to name but a few. How to compare these "celebrities" from history with the likes of Madonna, Pele, George Clooney and Lady Gaga?

They may have been lionized, idolized or even worshipped, but it was at a distance. They weren't in our living rooms. And they produced real, long-lasting achievements. Today's celebrities are more and more transitory. Paper lions, tin idols, and adored by a public that is seemingly incapable of recognising real merit, but is spoon-fed an inflated aura by a cynical media and a publicity system that will adopt the most intrusive of methods to achieve the maximum puffery.

Ellis Cashmore's first edition was published a mere 8 years ago, but such has been the explosion of this culture that it was more than ready for this updating. The author is professor of Culture, Media and Sport at Staffordshire University and despite what I have given as my opinion of media studies in another review in this issue of New Nurturing Potential, I can think of no better authority to have written this book.

I was somewhat surprised and disappointed to find the appended Timeline, which otherwise would have been an excellent and useful resource, to be printed in such miniscule format that - even with good eyesight - I could not read it. But then I spotted online a comment by Professor Cashmore that made some sense of this: " I also wanted to write a book fully-loaded for the digital age. In a sense this is a book written for the tablet-reader. The print edition is a parallel text, of course; but only by reading it on an iPad or a Kindle or other tablet will the reader get the full features."

Sep Meyer

Social Sciences - The Big Issues - by Kath Woodward. Paperback. 192 pages. £25.99 ISBN 9780415824095. Published by Routledge.

Social sciences is not one subject, it is a group of subjects that stand beneath the overall umbrella that is Sociology. They include issues of economics, geopolitics, public policy, ethnicity, and the environment. These can be very big issues and they loom large in the public arena. Furthermore they are changing and evolving more and more rapidly nowadays, a fact that is well demonstrated by the fact that Kath Woodward’s book, first published in 2003 needed revision in 2009, and now again in 2014.

Kath Woodward is Professor of Sociology with the Open University and is also connected with the Centre for Research into Socio-cultural Change; perfect credentials, I would suggest, for this exploration of the “big issues” that face citizens in this period of rapid change. She has divided this book into seven sections, the first of which is an introduction to the next five chapters, and the last of which is a review of the five chapters that precede it. Her introduction contains a very interesting use of a tower block in Sheffield as a microcosm for a study of the changes in society at this time.

In Chapter 2 she considers mobility issues, that is how communities are changing and how we identify ourselves within that mobile framework. Chapter 3 addresses current citizenship concerns, and considers inter alia the effects on our lives of greater European integration, increased immigration and the shifts in population, and the pressure this creates on welfare, health and education. Chapter 4 is entitled Buying and Selling and addresses questions of class, consumption and consumerism, including a interesting analogy between the 21st century experience and that described two centuries earlier in Emile Zola’s The Ladies’ Paradise.

In Chapter 5, Mobilities, Professor Woodward has considered the “interconnection between race and place” and the inter-relationship between race and gender, and the different impact these, and mobility and migration, have upon experience at other times and in other places. Her penultimate chapter is entitled Globalization and here she suggests that the defining aspect of this subject in the 21st century is the way human societies are being transformed across the globe.

This review has merely scratched the surface of a fascinating study by Kath Woodward and, seeing how great have been the changes in the past four years, one might perhaps (albeit tongue in cheek) suggest that Routledge may consider turning this into an Annual. In the meantime, just grab a copy and recommend it to your sociology students.

Terry Goodwin

Uncultured Pearls - by Joseph Sinclair. Paperback. 126 pages. Published by CreateSpace in the USA. (ISBN 9781500949723). Price US$8.96, and by ASPEN-London in the UK. (ISBN 978-0-9513660-7-3). Price £5.95.

It’s really hard to review a book of poetry. There are so many levels on which to judge it. Because poetry is mainly subjective you don’t know whether you should be looking for its “message”, or should you be considering how well the author has treated his works from the point of view of style or form. Has he succeeded in capturing my imagination or have I failed to find the message because it is too obscure?

Uncultured Pearls is no exception, but it does have a lot going for it. In the first place, Joseph Sinclair has provided such an illuminating social, personal and political commentary on his verse and the historical period in which it was written, that it has made it very interesting quite apart from the verse itself.

And as far as the poetry is concerned, it is obvious that he has put a great deal of effort into getting all the technical aspects of his verse correct. A lot of people prefer free verse, and often that is written rather quickly and without the effort that Joseph Sinclair has clearly put into his work. So, for that alone, he deserves praise. The other thing that I really enjoyed was his obvious sense of humour that he has brought to bear on so many of his poems.

I think there is a lot of pleasure and enjoyment to be obtained from this book, whether you think the verse is good or not, and I would certainly recommend that you have a look at it.

Curie Sofia Pereira

BIODATA OF REVIEWERS

Terry Goodwin was a senior marketing executive at Finexport Ltd in London and Bangkok until his retirement in 1992, since when he has been in private practice as

Joe Sinclair is Managing Editor of New Nurturing Potential as well as the presenter of Potential Unleashed. He is the author of twelve books including An ABC of NLP and co-author of Peace of Mind is a Piece of Cake. His latest book, published in August 2014, is entitled Uncultured Pearls and is described as 60 years of verse . . . and more!

Tara Jennett

is

a 17-year old

student at Bromley High School, where Nurturing Potential's Editor for the Arts,

Caroline Jenner, teaches English and Drama. Following the successful

review by one of her students in our last issue, Caroline had no hesitation in

offering this title when Tara expressed interest. Tara studies Art, Drama,

English and Biology at A-Level and is (at this time of writing) completing an

Outlook Expedition in Mongolia.

Mark Edwards lives in Exeter and works as a Primary Mental Health Worker in South Devon. He has a developing interest in working systemically and the focus of his work is with children and families. He runs a successful course for parents on Managing Challenging Behaviour

Sep Meyer is a graduate of the London School of Economics and, since his retirement from a commercial life, has occupied himself with writing poetry and drama, as well as articles in the area of sociology, politics and current affairs.

Michael Mallows coaches individuals and trains teams and groups in the voluntary, public and private sectors. He is the author of The Power to Use NLP and co-author of Peace of Mind is a Piece of Cake.

Penelope Waite retired from full-time teaching some years ago. She now divides her time between her homes in Brittany, France and south-west England. She continues to be interested in developments in education, particularly in special needs, and does some EFL tutoring in France.

Damlanur Abaan is a Turkish born Canadian who spends time in both countries. She is an internationally celebrated cook, a former restaurateur, and a follower of the Buddhist way.

Curie Sofia Pereira was born and educated in Goa and now lives in London, England.